A Cycling Motivation Story about Endurance

This blog post marks the first official Climb Mountains cycling story. I plan to release more content on similar topics to this one so be sure to click “Follow” at the bottom of the page to follow my blog for weekly postings. My plan is to revolve all of my stories around drawing inspiration and life advice tid-bits from cycling adventures.

Now, onto today’s story…

Last summer, my older brother, Kyle, and I set out to bike the entire distance of the Blue Ridge Parkway from North to South in about a week. We would carry all of various camping supplies, our tent, sleeping bags, food, and a camera across 475 miles and up and down 48,534 feet of elevation gain (for reference, the height of Mount Everest is 29,029 feet tall from sea level to summit). And we would do all of this in the insufferable heat of July.

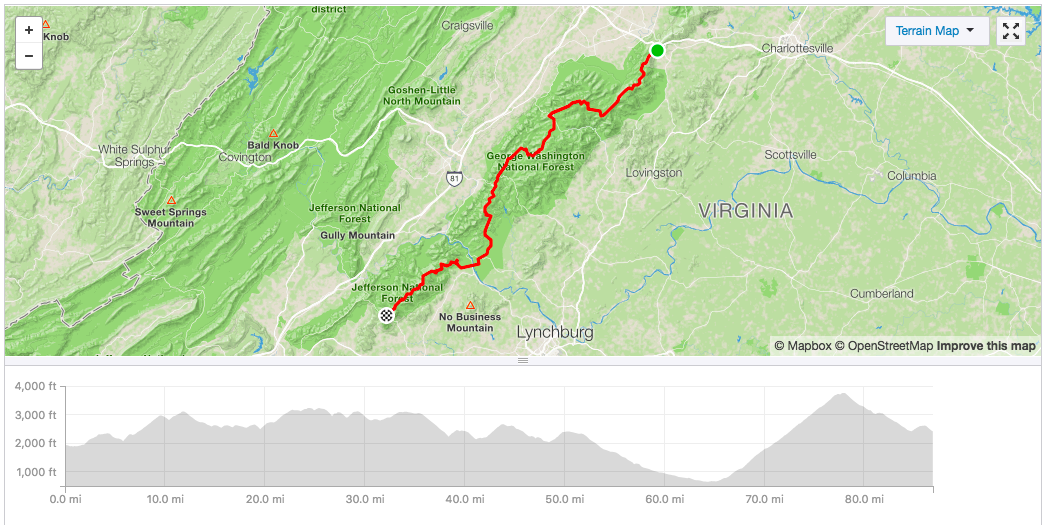

But the cycling adventure was almost over before it even began. On Day Zero of the trip, we arrived at the start of the Blue Ridge Parkway in Waynesboro, VA around dusk to pitch our tent. Day One dawned to two early-rising cyclists already out on the road to begin tackling the 86.91 miles and 8,518 feet of elevation for that day. We would roll through uphills and downhills until we came to the 50-mile mark. At this point, the road steadily descended for 10 miles until it reached the James River.

Approaching Thunder Ridge

We took a long break at the James River, nearly an hour or so. Having already completed 60 miles of our 80-mile day, we had one looming mountain directly ahead of us… Thunder Ridge. For the next 13 miles, we would climb 3,289 feet at an average gradient of 5%. Cyclists who live in the vicinity of Thunder Ridge know all about it. Many of them use its difficulty to train for even harder climbs. The “Storming of Thunder Ridge” is a local race that incorporates this climb as the crowning challenge. Even cyclists from abroad have been known to train on the grinding Thunder Ridge climb from time to time. I was familiar with it through the LU Cycling Team. Once a semester, it was Coach Parker Spencer’s trial by fire to welcome any new recruits and remind the veteran team members of the agony which is Thunder Ridge. I took my brother, Ryan, to Thunder Ridge to test our pannier set-up before our Colorado trip and he noted that the climb felt more challenging than the marathon he had recently run. It was definitely no small potatoes.

Why Climbing Mountains with Heavy Packs is Hard

Now let me just take a moment to explain some physics. When an object moves along a slope, the steepness of that slope determines how much gravity will affect the object’s acceleration versus how much friction will affect it. On a flat surface, a heavy object on wheels can roll fairly well once its initial inertia is overcome because, on a flat surface, the major opponent is friction and the wheels help to counteract that. Once the road begins to tick upwards, however, the main opponent becomes the force of gravity. You can picture this in exaggerated form by imagining how much effort it takes to lift a 200-pound object vertically versus sliding it around on a hand-truck.

The same principle applies to cycling, once elevation gain is introduced into the equation, weight is a very important factor. Bike companies work hard every year to design lightweight bikes designed specifically for hill-climbs while hill-climbing enthusiasts make modifications with some weighing as little as 10 pounds.

Our Packs were Too Heavy

My brother and I were definitely not riding 10-pound bikes. With our panniers and backpacks stuffed full of a week’s worth of food and camping supplies, we were riding very heavy. Having bought twice as much food as we needed for the trip, we had realized our mistake when packing up the day before. We tried to shed some of the heavier foods and redistribute the weight to even out the cumbersome loads so that no one tipped over when they came to stop.

Nevertheless, we still ended up with too much food and our loads were unwieldly. Our weight was not so much evident on the flat sections of road or the downhills but, as soon as the gradient shifted from 0% to 1% grade, we noticeable slowed down. Yet there we were, standing at the foot of a long, steady ascent in the hottest part of the day (my bike computer recorded a high of 104°F for that day).

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-wabfaqBOOY]

Beginning the Climb

When we felt good and ready, I reminded my brother of the gravity of what we were about to accomplish and assured him that we could take as many breaks as needed to climb this mountain. We didn’t last very long before we had to take a break… and then another… and then another… and then one more. Each time we got back on the bikes, our heart rates would climb and we would feel the fatigue setting in right away.

It was a grueling task, but we persevered. We crested the summit and were greeted with the respite of 6 miles of downhill. At this point, the road began to ascend again. We were two miles from our day’s destination. We had come 84 miles and tackled the hardest climb of the entire trip. We had toiled over a mountain that cyclists with much less weight considered challenging. We just had one more challenge to conquer and then we would be done.

Threatening to Quit

Kyle called for a break. We had filled up our water bottles at the James River and we were all out. He couldn’t go another step. I didn’t know it then, but he was starting to succumb to heat exhaustion. He told me that he felt sick and he wanted to go over what our options were. We always had our tent with us so that we could pitch up anywhere we wanted… in an emergency. We were also an hour’s drive from Lynchburg where our two sisters live and could come pick us up… in an emergency. His wife could drive all the way out here and pick us up… in an emergency. We could hitch-hike the remaining distance… in an emergency.

I wasn’t convinced this was an emergency. Having completed our first 96-mile bike ride in middle school, my younger brother, Ryan, and I have conquered harder and harder bike trips on a roughly every other summer basis. Summer 2016 was the first year we invited an outside member into our exclusive brotherhood by bringing along our older brother, Kyle, and his wife, Hannah, on our 700-mile bike trip through Colorado. Kyle rode with us through the majority of the Colorado trip, but his wife was driving the support vehicle and we made sure to give him permission to use it as a fail-safe option. We didn’t want to run the risk of being slowed down by any newbies.

With said newbie complaining of being on the edge of vomiting on Day One of the Blue Ridge Parkway Tour, I wasn’t convinced this was an emergency. We were two miles from our destination! I checked the map again. Uphill 200 feet for one mile. Downhill 200 feet for one mile. Then we’d be there. Done. I wasn’t quitting now, and I wasn’t going to let Kyle quit either.

Convincing Kyle to Keep Going

So, I did what I had to do. I stood up and gave him a motivational speech. I told him of Summer 2014 when Ryan and I had biked from Pittsburgh, PA to Washington, D.C. and Ryan had hit the figurative wall that all athletes are familiar with. It was dusk and we still had miles left to go on a 140-mile day. I told him of the points of difficulty which I had experience on various rides when I felt I couldn’t go much further. I told him what it felt like in those moments, how it felt like victory was impossible. It seemed like a matter of two plus two equals four. The impossibility of victory seems just as unlikely as the idea that two plus two can sometimes equal five or six or seventeen million. There is just no way for it to happen. It is a logical impossibility.

But we know now it did happen. We know now that we made it through. We know now that Ryan got back on his bike and finished that day’s ride back in 2014. And in the 20/20 of hindsight we can see so many impossible victories prove that they were indeed possible. Why can’t we always see ourselves from this hindsight perspective? Why can’t we visualize loafing around at our destination joking about how close we were to quitting? Why can’t we picture going home on the final day of the trip to tell everyone about how it was almost over before it ever began?

Kyle didn’t quite buy it. He was feeling really crummy. But he got up anyway and we biked the remaining distance to Peaks of Otter Lodge, our day’s destination. Kyle asked for a room in the hotel and explained to the receptionist that he was sick and in no condition to use the nearby campground. He then took a trip to the restroom. Then we sat down in the restaurant to eat.

Cooling Off Shocks His Body

I felt like a million bucks with all of those endorphins raging through my veins and ordered a hefty burger and a glass of coke. Kyle ordered a chicken sandwich with the salad bar. After poking around at his cucumbers a bit without making them disappear, he took another trip to the restroom. When the waiter came around with our food, I cheerfully informed him that my brother was currently vomiting or something and would probably require a box for his food. The waiter was slightly taken aback at the frankness of my nonchalant statement but I dug in to my meal and looked out through the window at the Peaks of Otter Lake which lay at the base of Sharp Top Mountain.

Medical Assistance Needed

When finished, I talked to the receptionist and discovered that she had sent my brother to his hotel room. She was getting out a large bag of medical supplies to walk over to the room with me. As a part-time nurse, she knew that Kyle’s condition was not very good. He was going through the stages following heat exhaustion when your body finally gets a chance to cool off and begins to go haywire. He was very feverish and dehydrated but he couldn’t keep down any liquids. He needed to drink water but he kept vomiting it all up. Through Divine Providence, she had anti-nausea medicine to help him begin to re-hydrate. She took his temperature and gave me strict instructions to call the lobby desk with an update about his condition. I followed her instructions but by 7pm, Kyle was fast asleep and there was nothing more to report. He woke up at 11pm, remarked that he was starting to feel better, called his wife and ate his chicken sandwich. Then he slept for 8 more hours after that.

The Remainder of the Blue Ridge Parkway Tour

We decided to shift our expectation for the rest of the trip. The next day we would sleep in as late as we needed to and then bike for 40 miles instead of the planned 80 miles. We would cut the Blue Ridge Parkway Tour one day short which would mean that we wouldn’t be able to complete the whole Parkway. We would bike a total of 407 miles and 40,987 feet of elevation and end in Asheville, NC. At the end of the trip, we still had food left over that we continued to eat for weeks afterward.

Kyle’s explanation of the events of Day One in the video below (at the 1min mark):

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TSTUPj1lxDY&w=560&h=315]

We had an overall great time on the Blue Ridge Parkway Tour 2017. But it would have been smarter from the beginning to have had more realistic expectations for Day One. This story, however, brings out the difficult balance between working hard and overworking. It was a trial by error in learning the difference between pushing our limits and knowing and respecting our limits. Sometimes this is not an easy lesson. When should we ignore all of our bodily complaints and motivate ourselves to keep moving? When should we take it easy and rest, and when does resting become laziness? (Also, maybe I just need to trust my brother when he says that he is on the verge of vomiting.)

Watch the Recap Video of the Blue Ridge Parkway Tour 2017 Here:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G2JBGaw7x5E]

***Thank you for reading my post. I would encourage you to share it with your friends. Maybe they will like it too. My blog is still gathering steam so I always notice and appreciate the little up-ticks in traffic that show that one or two more people have seen my blog posts. Every little share makes a huge difference.