Daniel Burton was the first man to bike to the South Pole. He was so kind as to talk to me about his trip. All quotes in this article are taken from our phone conversation.

Why Bike to the South Pole

Daniel Burton, now the first man to bike to the South Pole, found himself in a position that many can relate to. “I had been a computer programmer for quite some time and sitting at my desk not exercising as much I should. I wasn’t fat but I was heavier than I should have been.” He wasn’t unhealthy or obese in any particular sense of the word. He was living a comfortable and happy life. But a visit to the doctor revealed his blood pressure and cholesterol numbers were too high. He panicked and realized that he was going to die if he didn’t start making some changes. This was a wake-up call.

He tried to change his diet for several months but was continually frustrated that there was nothing that he could eat. Some friends of his got him into mountain biking. He was hooked and, when he was laid off of his programming job, he decided to open a bike shop.

When Daniel discovered fat bikes, a special type of mountain bike made for handling deep snow and ice, he had a moment of inspiration. He decided that he would bike to the South Pole. There was another man, Eric Larsen, a polar explorer, who had made a previous attempt in 2012. It was ultimately a failure when Eric had to turn back early at a quarter of the way in.

“But it proved that it was possible.”

Daniel was determined to finish what Eric had started and push through to the end.

The Determination of an Explorer

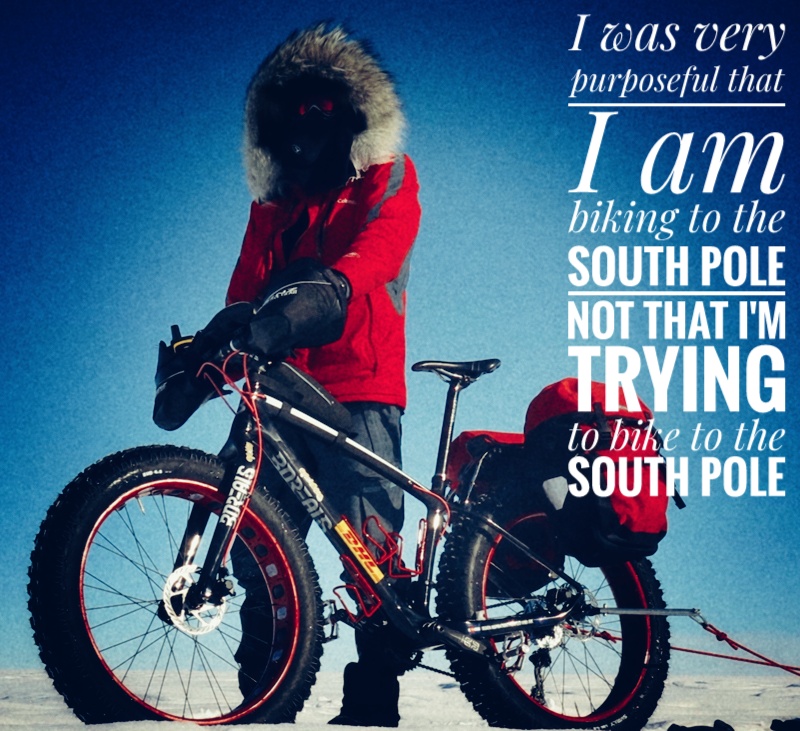

Daniel Burton believed that a rock-solid mindset was of utmost importance to the success of his mission. His determination was akin to that of the first man to ever reach the South Pole, Roald Amundsen, who said, “Our plan is one, one and again one alone–to reach the pole. For that goal, I have decided to throw everything else aside.” He began to talk about his intents to anyone who would listen with the assurance that he would unquestionably be the first to bike to the South Pole.

“I was very purposeful that I am biking to the South Pole not that I am trying to bike to the South Pole but that’s what I’m doing and I am doing this.”

“And I had some people criticize me saying, ‘you haven’t done it. You’re talking like as if you’ve already done it. Other people have tried and you will try and somebody after you will try.’ I wasn’t being arrogant but I was being purposeful in my attitude of success because I figured that that was a very important thing for me to be able to do it. If I did not have that attitude that I was going to do this, there was no way I was going to do it.”

Antarctica, The Formidable Foe

Daniel Burton knew that biking to the South Pole would be the hardest thing that he had ever done. “You know going into it, this is going to be harder than you could possibly imagine. No matter how hard you think it is, no matter how hard you can imagine, it’s harder.”

Antarctica is home of possibly the most extreme terrain and weather on Earth. The continent is shaped like a dome so that the center is higher than the edges. This cools the air at the center and, since cold air is more dense, sends it rushing downhill towards the coasts at a constant 40 mph. The wind does slightly let up and switch directions… during white-outs. White-outs are storms that hurl snow around so that you can’t see anything in front of you. It looks like the inside of a ping-pong ball. In one particularly bad white-out, Dan couldn’t see his own two feet and was tripping over the same snow drift a dozen times because he couldn’t see it.

Sastrugi pose an additional hazard. Hard-packed drifts in the snow scar the Antarctic terrain along the path to the South Pole and stand like frozen waves as tall as a man. On a bike, Daniel would sometimes roll along only to drop off the ledge of a sastrugi. But his path was marked by even deeper scars along his route. Crevasses where the 9-thousand-foot thick ice on top of the Antarctic land mass cracks were sometimes invisible until he was right overtop of them. At one point, he biked over a crevasse only to look back and see how much danger he had unintentionally avoided. He couldn’t take a picture for fear of falling in. Oh, and in addition to the wind, the white-outs, the sastrugi, and the crevasses, it was also cold; like -10 to -35 degrees Fahrenheit cold. Cold enough to freeze all of the moisture out of the air so that Antarctica has the technical distinction of being a desert.

Then there was the profound aloneness. There is absolute silence in Antarctica. There is nothing to make noise other than humans and Dan Burton was the only human for miles around. The wind is blowing across the ice but it isn’t making any noise because it’s not hitting anything. It looks like as if the edge of the world is 100 feet in any direction.

“You might as well be in the middle of the ocean”

But Daniel never felt fully alone. He believed that he had been given the opportunity to “walk with God” for 50 days. Often, in prayer, he would ask that God would remove the difficulty of his journey. In response, he was often given the opposite. The headwind would get stronger or a new obstacle would threaten his progress. The point was clear. This was his journey. He was given these obstacles. They were his task to overcome. Relief from his trials was not the solution, conquering the impossibility of his task was what he came here to do.

No Room for “Try”

“Take the most difficult thing you can possibly imagine and do that for 51 days and then make it twice as hard and keep going… and it’s worse than that.”

He knew the danger. He knew the difficulty. Yet he believed that he could not give himself room to merely try. He had to operate on confidence. He had to set his mind straight, from the beginning, to know that he would push as far along as he was physically capable of. There would be no half-measures.

“I don’t think I was ever thinking about calling it quits. There were points where I didn’t think I was going to make it. But before I left, I made it a point to really work on the idea that I was not going to quit no matter what. And so I had already decided that I was not going to. Maybe a week or so in and I had been covering maybe, at best, 5 to 7 miles a day, and it was pretty obvious at that time that there was no way I was going to make it to the South Pole at that rate. So I had called my wife and I had told her I’m not going to make it but I had decided that I was going to continue on as far as I could.”

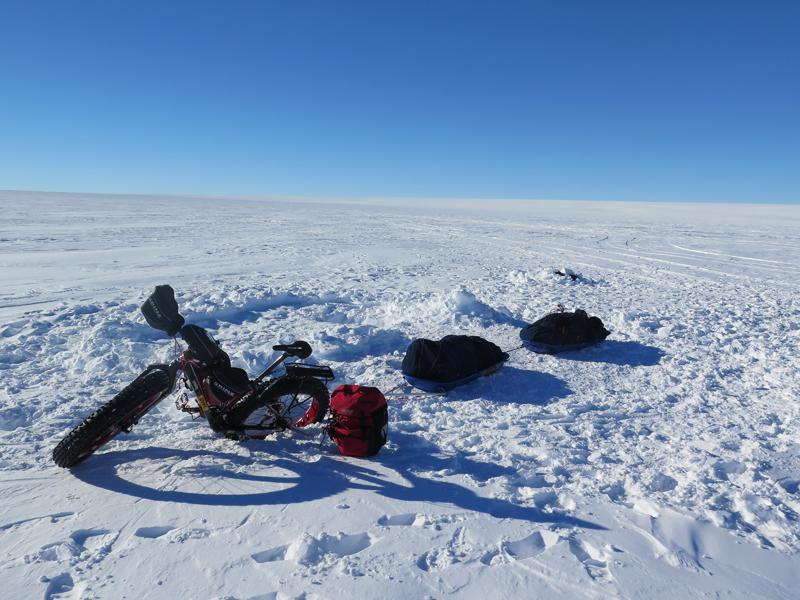

The Angus MacGyver of the Antarctic

It was slow-going progress. Despite his fat bike being specially designed to handle snowy conditions and the fact that he kept the tire pressure low to further aid his traction, he still only crawled along. He pulled his supplies behind him in two sleds to distribute the weight so as to move along the ice without sinking in. The rolling hills of Antarctica trend upwards towards the Pole with a few, barely noticeable downhills mixed in. At one point, he threw his GPS across the ice in frustration because it kept telling him that he was going downhill when it sure didn’t feel like it.

Partway into the trip, his bike began to fail him. The freehub fell apart. So he wrapped some derailleur wire around the spokes to reattach the freehub. When this jury-rig inevitably gave out, he used some wires from his pack to do the trick. Eventually, all the wires broke. At that point he asked himself, “What am I going to do?” Then he thought to himself, “You know if you wanted to get out and say, ‘I didn’t fail. My bike failed,’ you could get out gracefully.” But, “In less time than it takes to explain it and think about it, I had already decided that I was going and so I was going to keep going.” At that point, he remembered that there was a bit of wire in his parka hoodie and in the windows of his tent to shape the fabric. He teased out the wire and used that to keep his freehub on so he could keep biking until his supply dropper could drop a new wheel to him.

The South Pole in Sight

A full day or two before he reached the South Pole, Daniel Burton was watching his GPS. Looking at the elevation reading, he knew that when he reached 9,300 feet, he would be at his journey’s end. Off in the distance, there were three black dots on the white horizon. Sure enough, he had made it.

“That, for me, it was so overwhelming that there it was after all of the work that I had put into it. Sometimes you doubt yourself and think that you never will succeed. You think, ‘I’m not going to make it. It’s just another thing I’ve failed at.’ You can see it and you have succeeded and the joy is so amazing and I will go back and get to see my family. I had been all alone for over 2 months and now it was finally over and I had done it. It was beyond description. I have never felt so happy in my life and I’m breaking down in tears and calling my wife. I was trying to tell her that I could see the South Pole and I could hardly tell her.”

“So then I had to keep going but kept my head kind of turned to the left because the glimpse of those three dots was so overwhelming. It was so cool that I had made it.”

“There is kind of a dip between that point and the South Pole and you drop into this bowl. I spent 24 hours straight, on that last day, going the rest of the way.”

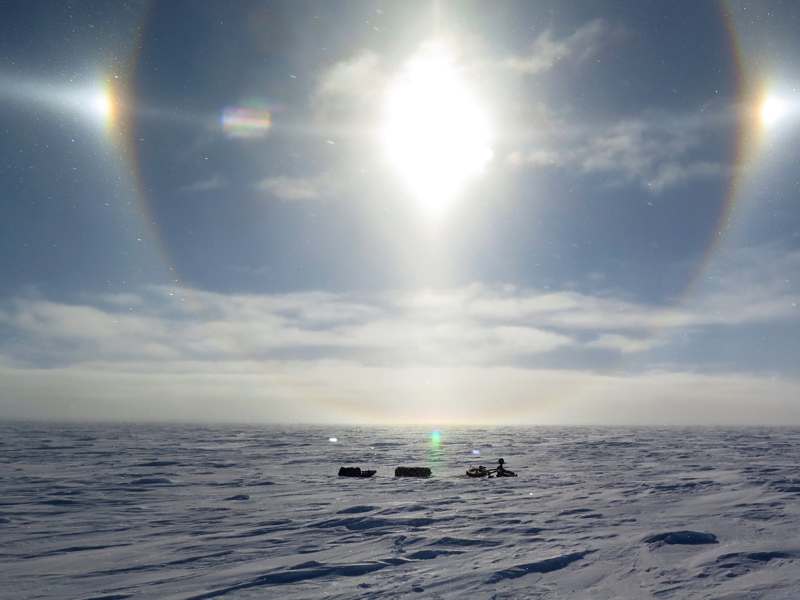

That last day, he looked around at his surroundings and took it all in knowing that he had made it and it was now his last opportunity to admire his environment. Setting foot on Antarctica was a unique experience. After 51 days, 750 miles, the silence of the cold, the wind, and the drifts of snow now seemed like familiar friends. The endless summer sun, shining through the ice crystals in the air, formed a double circular rainbow as it rounded the sky in 24-hour daylight. He ceremonially posed at the candy cane pole that, due to shifts in the ice over the years, was no longer geographically accurate.

A Page in History

Daniel Burton’s accomplishment was significant because it was a first. No one had ever biked to the South Pole solely on a bike. It shows how far bike engineering has come that these simple machines are able to take on the Antarctic terrain. But, more than that, Burton’s South Pole journey was a testament to the determination of the human will. It showed the borderline foolhardiness of a dream that achieved bigger goals than more experienced expeditioners. It’s a story of how an otherwise ordinary computer programmer stepped into a role beyond what he could have imagined himself doing. It’s a call to dream big and swing for the fences.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1D5NK5vf0I&w=560&h=315]

Buy Dan Burton’s book on Amazon

Check out his blog here