A Life Lesson from Cycling

I don’t care about most of the reasons why you should start commuting to work on a bicycle. You have probably heard them all before anyways. Such as how it might help the environment. You might have heard about the fitness implications or maybe even how it releases endorphins in your brain. That sounds good and all. I’m sure that the environment will send an envoy of happy trees to stiffly shake your hand. And being physically fit and happy everyday never hurt anyone.

But, having used a bicycle as my main transportation for the past 7 years, I want to share this one reason with you. Surprisingly, it has very little to do with cycling itself.

The other reasons why you should commute by bike are well and good. But they aren’t what really got me on the bike at 5:30am. They aren’t what pushed me to bike though freezing rain at 2am or to finish off an exhausting 14 hour night-shift biking through a snowstorm up a steep hill. After a full day of college classes intermixed with intense triathlon training followed by a long night at McDonald’s, I don’t think that there is a single environmentally-conscious sentiment that would turn those pedals.

So what’s been driving me to such insanity for so many years in so many circumstances?

In a Word: Efficiency

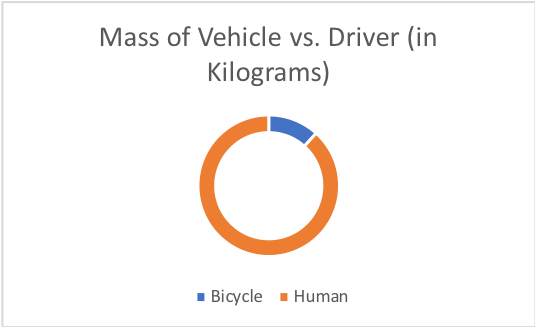

A simple physics equation for moving a given object from Point A to Point B states that Force = Mass x Acceleration. This means that the amount of force necessary to move an object is equal to its mass multiplied by its acceleration. For comparing modes of transportation, we can look at the force necessary to accelerate a bicycle down the road. This equals the cyclist’s and bicycle’s combined mass multiplied by the rate of acceleration. This gives us the force necessary to move the bicycle. My bicycle weighs around 20lbs (9kgs) and I weigh around 150lbs (68kgs) to give a total weight of 170lbs (77kgs). The equation is visualized here:

In the “m”, the blue represents my mass as a rider. The red represents my bicycle’s mass. As you can see, of the amount of mass that I am moving, I make up the bulk and my vehicle (i.e. the bicycle) makes up only a small portion.

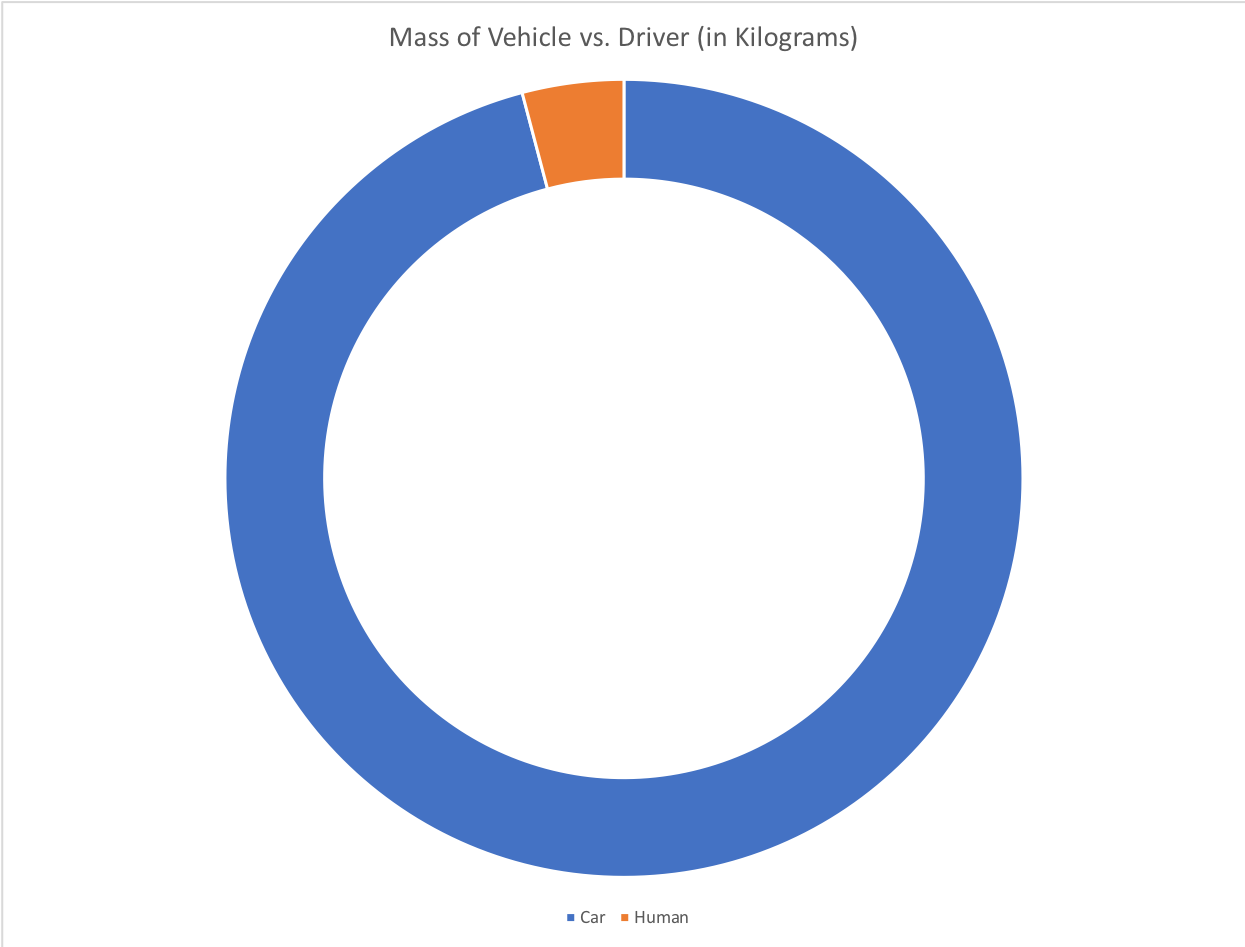

For an automobile, on the other hand, that proportion of rider’s mass to vehicle’s mass turns itself inside-out. An average mid-size car weighs in at 3,500 lbs.(1587kgs). Of the total mass of the vehicle plus driver, my mass accounts for only 4.1%. This means that the amount of force that the car expends to accelerate at the same rate as the bicycle is significantly larger… 21.5x larger, in fact. In the illustration below (not to scale), the red in the “m” represents the car’s mass and the blue represents my mass.

So to accelerate me down the road at the same rate as I do on my bicycle, my car has to expend 21.5 times as much force AND 95.9% of that force is spent on just moving the car itself. All of that just to accelerate at the same rate as the bicycle. The numbers become even more dramatic if I were to accelerate faster than the bicycle. And then I would have to start figuring in friction and aerodynamic drag and how much energy is lost to heat and all that math. The point stands just as well on its own.

Just take a moment to look at these charts and think about how massive your car is compared to how little you, the most important part, are. You’re like the only payload on a lengthy freight train. Would you want to run a whole freight train with only one of its train cars full?

Why does It Matter?

Efficiency is all about doing more with less. Maybe, to the individual who sees cars as the only option, it may not matter. So long as gas prices don’t shoot through the roof and they keep car repairs to a minimum, they can control damage to their wallet. And, if they can afford it, why not enjoy the simple luxury of getting from point A to point B in a climate-controlled and comfortable ride. Maybe point A and point B are too far away to make the trip on a bicycle. Maybe they have a valid excuse to drive a car. It’s not so much of luxury. After all, the number of drivers in the U.S. far exceeds the number of cyclists. Everyone drives. Why put in the extra legwork?

Maybe so. But, then again, maybe not. Maybe you find yourself in a different circumstance altogether. You don’t have the proper resources. You don’t have enough education, the right skills or deep enough pockets. You live in an economy built around scarcity and are desperately trying to become a hoarder. You live in a materialistic world without the materials you think you need and you have no way to acquire them. You are grasping at air trying to catch up, only to realize the constant limiting factor… you don’t have the stuff.

To such a person, cycling is more than commuting, it is liberation. It tells you that you don’t need more resources, you need more legwork. It’s the idea that it doesn’t take stuff to start your life. It takes you. It takes your passion, your energy, your power. This is why I fell in love with commuting by bicycle. It was a constant reminder of how much money I wasn’t wasting on unnecessary comfort. I took what looked like a necessity and, because I knew what I could do without it, I mentally relabeled it as a luxury. It reminded me that with a little extra effort, I don’t need as much stuff as I think I need.

The Bottom Line

Writing this post, I don’t wholly care if you decide that commuting by bicycle is right for you. Everyone’s situation is different and you need to pick the best mode of transportation to suit your needs. But what I do care about is this: there are “bicycles” all around you. There are examples all over the place of lost efficiencies in the choices you make. You could spend all day beating your head against a wall while the simplest “hack” sits right beside you. Maybe the last thing you need to soothe your frustration is more stuff. You will never learn to do more with less when everything is at your finger-tips. What you might really need is fewer resources so that you can start evaluating where you are really investing your efforts. Maybe you are wasting more energy moving the thing that should be moving you. Maybe you don’t have the stuff and maybe that’s a good thing.